Sargon Boulus

Details

- Artist Type

- Poet

- Biography

-

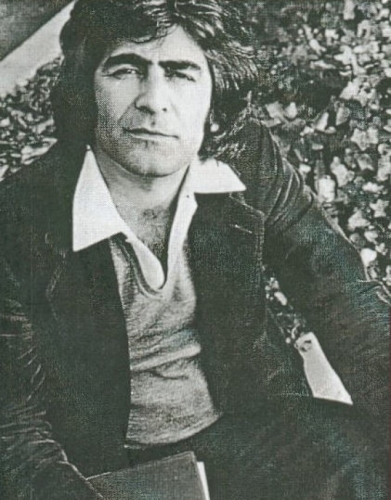

Sargon Boulus (1944 – October 22, 2007) was an Iraqi-Assyrian poet and short story writer.

He was born in Habbaniyah, Iraq. In 1967, he left for Beirut, where he worked as a journalist and a translator. He later emigrated to the United States, and from 1968 lived in San Francisco. He studied comparative literature at the University of California at Berkeley, and sculpture at Skyline College. An avant-garde and thoroughly modern writer, his poetry has been published in major Arab magazines and has translated W. S. Merwin, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, and others.

Sargon was born to an Assyrian family in the British-built 7-mile enclave of Habbaniya, which was a self-contained civilian village with its own power station on the edge of a shallow lake 57 miles west of Baghdad, Iraq. From 1935 to 1960, Habbaniya was the site of the RAF (Royal Air Force) and most of the Assyrians were employed by the British, hence the English language fluency by most Habbaniya Assyrians. Sargon's father worked for the British, as the rest of the men in the village, and the place of Sargon’s first cherished memories. On rare occasions Sargon would accompany his father to work and he would be fascinated with the English women in their aristocratic homes, “having their tea, seemingly almost half-naked among their flowers and well-kept lawns” (Sargon, page 16) 1. This image was in such contrast to the mud huts where the Assyrians lived and different from the females he was surrounded by who were dressed in black most of the time. Sargon recalls, “I've even written about this somewhere, some lines in a poem. Of course I wasn’t aware at the time that they were occupying the country, I was too young”2.

In 1956, Sargon’s family moved to the multi-ethnic large city of Kirkuk, his first experience with displacement. Among the Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Turkmon and Assyrians, Sargon was able to communicate in the two languages spoken at home, Assyrian and Arabic. His poetry resonates with the influence of this period in his life, embracing the Iraqi cultural multiplicity.

Sargon found his talent for words at an early age and Kirkuk’s rich diverse community inspired his work. He was an avid reader but never great at academics. Sargon had access to western literature due to another British presence in Iraq, The British Iraqi Petroleum Company (IPC). Again every Assyrian household had at least one family member working at IPC. In addition to Arabic and East European literature, he read James Joyce, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Sherwood Anderson. Franz Kafka, Czeslav Milosz and all the Beat writers were some of his favorites and poetry was the guiding light.

Sargon started publishing poems and short stories as a teenager in various Iraqi journals and magazines, and started to translate American and British poetry into Arabic. As he became recognized among his peers, he eventually sent his poetry to Beirut where they were published in the prominent publication Shi`r (Poem, in Arabic). Through many tribulations, Sargon travelled by land and mostly by foot from Baghdad to Beirut where he met his lifelong colleagues and fellow poets. From there he was clever enough to talk the American ambassador into allowing him entry to the USA where he made San Francisco his base for almost four decades. He lived a quiet life of an artist, writing poetry and sometimes painting. Although he was not recognized as a painter, he did manage to create a significant body of work with oil paintings and collages. In fact his paintings have never been made public.

The combination of a rich Assyrian-Iraqi heritage and exposure to a variety of literary classics enabled Sargon to develop a unique poetic style and a worldview that was uncommon in the 1960s Iraqi poet community. Over time his style emerged to a tepid reception in part due to his departure from the traditional structure of his contemporaries. While free verse poetry had been in use for hundreds of years, it was considered to be modern and unconventional. Sargon Boulus was very aware of his gift for writing and consequently he did not want to be branded as an ethnic or political writer, rather a humanist “mining the hidden areas of what has been lived through” (Boulus, page 15) 1. Poets continue the work of past poets and Sargon considered himself part of that chain of privileged messengers of words. His inspiration emanates from the work of poets spanning from ninth century Abu Tammam to Wordsworth, Yeats, W. C. Williams and Henry Miller just to name a few. Memories nurtured his themes, particularly childhood impressions. “What guides my steps / to that pool hidden / in the country / of childhood” (Boulus, page 70) 1. He believed that people’s pasts are permanently engraved in their memory waiting to be rediscovered again at some point in time. With aspirations for expressive freedom Sargon veered away from political and nationalistic discourse. He desired to express the truth about all human struggles without the influence of racist and religious tension. Sargon was a Universalist. The dictionary defines Universalist as: a person advocating loyalty to and concern for others without regard to national or other allegiances. Source

Sargon Boulus (1944 – October 22, 2007) was an Iraqi-Assyrian poet and short story writer.

He was born in Habbaniyah, Iraq. In 1967, he left for Beirut, where he worked as a journalist and a translator. He later emigrated to the United States, and from 1968 lived in San Francisco. He studied comparative literature at the University of California at Berkeley, and sculpture at Skyline College. An avant-garde and thoroughly modern writer, his poetry has been published in major Arab magazines and has translated W. S. Merwin, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, and others.

Sargon was born to an Assyrian family in the British-built 7-mile enclave of Habbaniya, which was a self-contained civilian village with its own power station on the edge of a shallow lake 57 miles west of Baghdad, Iraq. From 1935 to 1960, Habbaniya was the site of the RAF (Royal Air Force) and most of the Assyrians were employed by the British, hence the English language fluency by most Habbaniya Assyrians. Sargon's father worked for the British, as the rest of the men in the village, and the place of Sargon’s first cherished memories. On rare occasions Sargon would accompany his father to work and he would be fascinated with the English women in their aristocratic homes, “having their tea, seemingly almost half-naked among their flowers and well-kept lawns” (Sargon, page 16) 1. This image was in such contrast to the mud huts where the Assyrians lived and different from the females he was surrounded by who were dressed in black most of the time. Sargon recalls, “I've even written about this somewhere, some lines in a poem. Of course I wasn’t aware at the time that they were occupying the country, I was too young”2.

In 1956, Sargon’s family moved to the multi-ethnic large city of Kirkuk, his first experience with displacement. Among the Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Turkmon and Assyrians, Sargon was able to communicate in the two languages spoken at home, Assyrian and Arabic. His poetry resonates with the influence of this period in his life, embracing the Iraqi cultural multiplicity.

Sargon found his talent for words at an early age and Kirkuk’s rich diverse community inspired his work. He was an avid reader but never great at academics. Sargon had access to western literature due to another British presence in Iraq, The British Iraqi Petroleum Company (IPC). Again every Assyrian household had at least one family member working at IPC. In addition to Arabic and East European literature, he read James Joyce, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Sherwood Anderson. Franz Kafka, Czeslav Milosz and all the Beat writers were some of his favorites and poetry was the guiding light.

Sargon started publishing poems and short stories as a teenager in various Iraqi journals and magazines, and started to translate American and British poetry into Arabic. As he became recognized among his peers, he eventually sent his poetry to Beirut where they were published in the prominent publication Shi`r (Poem, in Arabic). Through many tribulations, Sargon travelled by land and mostly by foot from Baghdad to Beirut where he met his lifelong colleagues and fellow poets. From there he was clever enough to talk the American ambassador into allowing him entry to the USA where he made San Francisco his base for almost four decades. He lived a quiet life of an artist, writing poetry and sometimes painting. Although he was not recognized as a painter, he did manage to create a significant body of work with oil paintings and collages. In fact his paintings have never been made public.

The combination of a rich Assyrian-Iraqi heritage and exposure to a variety of literary classics enabled Sargon to develop a unique poetic style and a worldview that was uncommon in the 1960s Iraqi poet community. Over time his style emerged to a tepid reception in part due to his departure from the traditional structure of his contemporaries. While free verse poetry had been in use for hundreds of years, it was considered to be modern and unconventional. Sargon Boulus was very aware of his gift for writing and consequently he did not want to be branded as an ethnic or political writer, rather a humanist “mining the hidden areas of what has been lived through” (Boulus, page 15) 1. Poets continue the work of past poets and Sargon considered himself part of that chain of privileged messengers of words. His inspiration emanates from the work of poets spanning from ninth century Abu Tammam to Wordsworth, Yeats, W. C. Williams and Henry Miller just to name a few. Memories nurtured his themes, particularly childhood impressions. “What guides my steps / to that pool hidden / in the country / of childhood” (Boulus, page 70) 1. He believed that people’s pasts are permanently engraved in their memory waiting to be rediscovered again at some point in time. With aspirations for expressive freedom Sargon veered away from political and nationalistic discourse. He desired to express the truth about all human struggles without the influence of racist and religious tension. Sargon was a Universalist. The dictionary defines Universalist as: a person advocating loyalty to and concern for others without regard to national or other allegiances. Source